Shingles Vaccine Linked to Lower Dementia Risk, Landmark Study Finds

A new study published in Nature on April 3, 2025, reveals compelling evidence that the shingles vaccine may significantly reduce the risk of developing dementia. The research, led by Stanford University medical experts, leveraged a unique aspect of Wales’ vaccine rollout to produce some of the strongest causal data yet connecting vaccination and lowered dementia rates.

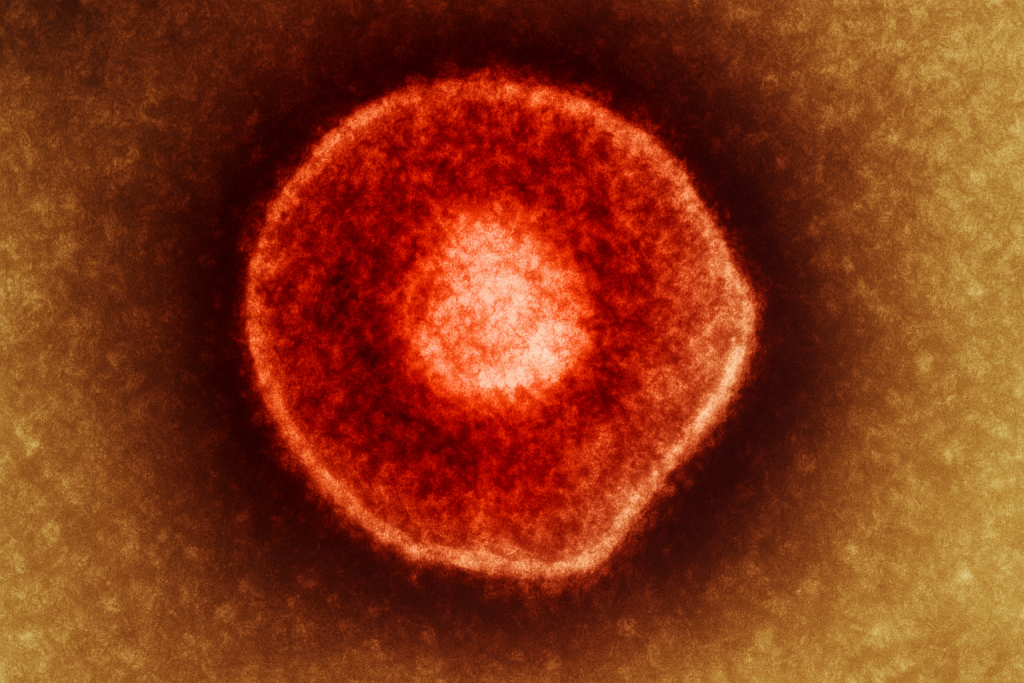

Shingles, caused by the varicella zoster virus (the same virus behind chickenpox), affects adults who have previously contracted chickenpox. After an initial infection, the virus can lie dormant in the nervous system for decades before reactivating, leading to painful, blistering rashes. Increasing evidence suggests that viral reactivation, including that of varicella zoster, could contribute to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s by promoting the formation of amyloid plaques, a key pathological feature of dementia.

Testing this theory has traditionally been challenging due to the difficulty of distinguishing correlation from causation. However, the Stanford team utilized a natural experiment created by Wales’ shingles vaccination policy. Starting on September 1, 2013, Welsh citizens aged 79 and under were eligible for the vaccine for one year, while those aged 80 and over were not, due to limited vaccine supplies. This policy effectively created two demographically similar groups divided only by vaccine eligibility based on their exact birth date.

The researchers analyzed detailed health records from 282,541 adults who fell just on either side of the cutoff. Participants who had been diagnosed with dementia prior to 2013 were excluded. By the end of the seven-year follow-up in 2020, one in eight had been newly diagnosed with dementia. Strikingly, those who had received the shingles vaccine were 20% less likely to develop dementia compared to their non-vaccinated counterparts.

Previous studies have hinted at such a connection, but confounding factors, such as differences in education, socioeconomic status, or health-seeking behavior between those who opt for vaccination and those who do not, made it difficult to prove. The Welsh policy circumvented these issues, providing a rare, quasi-randomized structure that strengthened the validity of the findings. The vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups were statistically identical in key characteristics beyond vaccine receipt, including levels of education, opioid use, and the prevalence of other health conditions.

Further bolstering the study’s conclusions, the team found that individuals who had experienced multiple shingles episodes were more likely to develop dementia. However, the use of antiviral treatments during shingles outbreaks appeared to mitigate this risk. This finding aligns with a biological model in which viral reactivation triggers neurotoxic inflammation, amyloid-β deposition, tau aggregation, and vascular damage, hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Anupam Jena, a Harvard health care policy expert not involved in the research, praised the study in a commentary for Nature News and Views, noting its strength in mimicking the structure of a randomized controlled trial. “Reactivation of the virus is thought to cause amyloid-β deposition, tau aggregation, and damage to blood vessels, key features of Alzheimer’s disease,” Jena explained.

Stanford medical professor Pascal Geldsetzer, who led the research team, confirmed that similar analyses are underway in England, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, where vaccine rollouts followed comparable age-based eligibility rules. Geldsetzer reported that preliminary data from these countries also show a “strong protective signal for dementia,” though these additional findings have not yet been published.

While the study stops short of definitively proving that shingles causes dementia or that the vaccine guarantees protection, it offers some of the most persuasive evidence to date supporting the theory that viral infections could be critical contributors to neurodegenerative disease. It also opens the door for future research into how vaccines against latent viral infections might serve as unexpected tools in the fight against dementia.

The study represents a significant step forward in understanding the potential broader benefits of vaccination beyond their immediate, intended effects.